The President pled with Chinese dictator Xi Jinping for local diplomatic support defaulted national security concerns with his own re-election chances and dismissed Beijing’s violations of human rights.

The U.S. tactic towards the republic of china has been based on two necessary proposals for more than four decades. First is that the Chinese economy will be irrevocably changed by economic recovery due to market-oriented policies, increased foreign direct investment, ever-increasing linkages with global markets, and broader acceptance of universal commercial, moral codes. Trying to bring China into the World Trade Organization became the embodiment of this appraisal in 2001.

The second assumption is that, as China’s national expense on the income, its ideological inclusiveness would largest spending. When China becomes more competitive, rivalry for global or regional supremacy will be reduced, as well as the possibility of international conflict — hot or cold — will fade.

Both proposals were patently wrong. After entry into The WTO, China did the exact opposite of what had been anticipated. China has been playing the organization, trying to pursue a mercantile policy in a supposedly free-trade body. China confiscated copyrights, demanded technological transfers from international firms, and proceeded to control its economy in oppressive ways.

Socially, China has stepped away from socialism, not from the democratic system. China seems to have its more popular figure in Xi Jinping and its most central power since Mao Zedong. Racial and theological oppression persists on a large scale. In the meantime, China has set up a formidable cyber-war objectionable system, built a blue-water military for the first time in 500 years, doubled its Everton of atomic warheads and missile systems, and much more.

I have seen these advancements as a danger to U.S. national security interests and to our partners and neighbours. Essentially, the Obama administration set and watched it occur.

In certain ways, President Donald Trump represents the increasing anxiety of the United States regarding China. He cherishes the key reality that military and political power lies in a growing economy. Trump often claims that trying to stop China’s unreasonable economic development at America’s cost is the best way to destroy China, which again is fundamentally right.

Yet the main issue is what Trump is thinking about China’s challenge. His advisors are mentally seriously broken. The regime has “panda huggers” like secretary of the Treasury Steven Mnuchin; verified free-traders like National Economic committee Director Larry Kudlow; and China hawks like Trade Secretary Wilbur Ross, exchange negotiator Robert Lighthizer and White House Trade Advisor Peter Navarro.

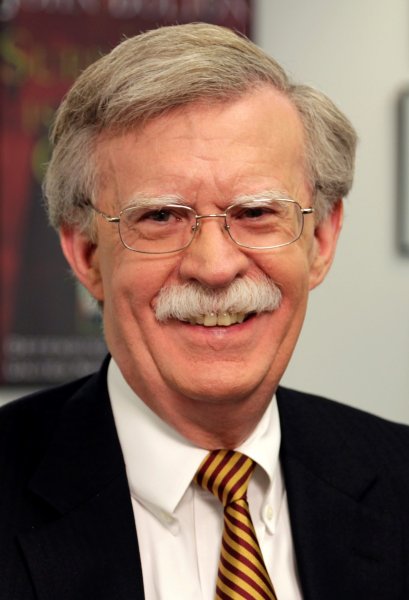

When I became Trump’s National Security Advisor in April 2018, I would have the most pointless position to play: I had to place China’s trade policies in a wider geopolitical context. We had a great motto, trying to call for an open and free Indo-Pacific region. Yet the bumper sticker is not a tactic, so we have failed to stop getting pulled into the dark pit of US-China trade problems.

Economic affairs have been dealt with in a totally disorderly manner since day one. Trump’s favourite action to take was to bring small hoards of lawyers together, in either the white house or in the Roosevelt Room, to raise these complex, controversial subjects. The same things, over and over again. Without a resolution, or worse, one outcome one day, and the opposite end result in a few days later. The entire thing hit my brain.

With mid-term elections approaching in November 2018, little progress was made on China’s trade front. Attention was given to the forthcoming G-20 summit in Buenos Aires the next month, where Xi and Trump could meet in person. Trump sees that as a vision in his fantasies, of the two major players coming together, putting the Europeans behind, cutting off the whole deal.

What might have gone wrong? Lots, in the view of Lighthizer. He became really concerned about just how much Trump became going to offer up until undeterred.

At dinner in Buenos Aires on Dec. 1, Xi started by showing Trump how good he was, placing it on the heavy. Xi was reading through note cards on a steady basis, without hesitation, all of it had worked hard ahead of time. Trump’s ad-libbed, with no one from the U.S. side realizing what he ‘d say through one minute to another.

Yet another high point happened to come when Xi said he needed to pursue with Trump for another six years, and Trump responded that people have been saying that the two-term legislative threshold on senators should be lifted. Xi claimed the U.S. has so many votes and he didn’t want to a step further from Trump, who smiled appreciatively.

Xi eventually started to shift to substance, characterizing China ‘s position: the US would roll back Trump’s tariff rates, and both sides would refrain from competing for economic espionage and concur to not participate in malicious hackers (how thoughtful). The U.S. would remove Trump’s tariffs, Xi said, or at least decide to abandon current concepts. “people expect this,” said Xi, and I was afraid at that time that Trump will also merely say yes to all that Xi had sketched out.

Trump got close, arbitrarily providing that US tariff barriers will also continue to stay at a percentage of 10 rather than rise to a percentage of 25, as he had originally attacked. In return, Trump meant to call for any raise in Chinese farm-product sales to assist with the critical agricultural-state vote. If it could do agree, all U.S. tariffs would be decreased. It’s been stunning.

Trump asked Lighthizer if he had left something out, and Lighthizer tried all he could to bring the discussion back to the true level, dwelling to logistical problems, and breaking the Chinese idea apart. Trump shuttered by saying that Lighthizer would have been in control of the agreement-making process, and Jared Kushner will also be engaged, at which time all of the Chinese were persuading and smiling.

The deciding game came in May 2019, when the Chinese renounced a number of key elements of the evolving contract, along with all the structural problems. This was proof to me that China was merely not severe.

Trump has spoken to Xi by mobile on June 18, only about one week ahead of the G-20 summit in Osaka, Japan, in which they would meet next. Trump started by telling Xi he did miss him and said that the most common area he ‘d ever been implicated in was a trade deal with China, which would have been a massive bonus for him ideologically.

At their meeting in Osaka on June 29, Xi assured Trump that the partnership between the US and China was the most significant one in the country. He said that certain (unnamed) American political figures were taking wrong decisions by pushing for a fresh Cold War with China.

If either Xi meant fingering the Democrats and some of us lounging on the U.S. end of the desk, I don’t know, and yet Trump assumed that Xi meant the Democrats. Trump claimed that there was considerable animosity amongst the Republicans to China. Trump instead, astoundingly, switched the topic to the forthcoming United States presidential election, referring to China’s economic potential, and negotiating with Xi to make sure he succeeded. He stressed the value of farmers and expanded the Chinese purchasing of soya beans and grain in the election period. I would publish the words exactly of Trump, but the government’s pre-publication review process has chosen anything else.

Trump after which brought about the crash of the trade talks last month, imploring China to come back to the roles it had recanted as well as draw the conclusion a most thrilling, greatest thing already. He indicated that the US would not place sanctions on the existing $350 billion in trade deficits (by Trump’s arithmetic), yet he referred to allowing Xi to purchase as many American agricultural goods as China might.

Xi did agree that we must continue trade talks, welcome Trump’s agreement that there will be no new tariff barriers, and concur that the two negotiating teams must continue conversations on agricultural products on a large scale. “You’ve been the biggest Chinese captain in 300 years! “Rejoiced, Trump changed that to” the best manager in Chinese history “a few moments later.

Consequent agreements again when I stepped down led to an interim “deal” unveiled in December 2019, but that’s less than eye-catching.

Trump’s discussions with Xi mirrored not just the inconsistency of his international trade, as well as the combination of his own commercial reasons and U.S. national security interests in Trump’s mind. Trump combined both the individual and the global, not only on trade issues but all over the entire landscape of global defence. It’s hard for me to identify any significant Trump choice all through my White House tenure that’s not pushed by re-election computations.

Take Trump’s management of the dangers posed by the Chinese telecom companies Huawei and ZTE. Ross and many others have increased commercial the strict enforcement of U.S. regulations and criminal laws against improper misrepresentation, such as the violation by both firms of the U.S. sanctions against Iran and other rogue states. A most important objective for Chinese companies such as Huawei and ZTE is to subvert information technology and information technology systems, particularly 5 G, and to subject them to Chinese control (though, of course, both firms refute the U.S portrayal of their operations).

Trump, on the other side, viewed it not as a substantive question to be addressed, but as an opening to render private concessions to Xi. In 2018, for instance, he overturned the fines that Ross and the Department of Commerce had put on ZTE. In 2019, he provided to overturn federal indictment against Huawei if it helped in the trade agreement — that also, of duration, was mainly regarding obtaining Trump re-elected in 2020.

All these countless other comparable discussions with Trump established a sequence of inherently poor behavior that undermined the very the validity of the presidential term. Would have a representative democracy indictment advocates not been so obsessed with their Ukraine blitzkrieg in 2019, had they chosen to take the time to look more systematically at Trump ‘s behavior across his the whole foreign policy, the indictment outcome might well have been different.

As trade discussions continued, Hong Kong ‘s dissatisfaction with China’s harassment was continuing to grow. The deportation constitution includes the spark, and mass demonstrations were ongoing in Hong Kong by early June 2019.

I first heard Trump respond on June 12, when he noticed that some 1.5 million people had taken part in Sunday’s protests. “This is a big deal,” he said. Yet he quickly said, “I don’t want to be embroiled,” and, “We do have human rights problems.”

I was hoping that Trump will see these advancements in Hong Kong as offering him leverage over China. I was expected to learn something. That same month in China’s tragedy, on the 30th anniversary of pro-democracy protesters in Tienanmen Square, Trump refused to offer a White House statement. “That was 15 years ago,” he said incorrectly. “Who cares about it, huh? I’m going to make a bargain with you. I don’t want anything. “And that’s it.

Beijing’s suppression of its Uighur residents has also continued rapidly. Trump told me at the 2018 White House Christmas dinner if we were contemplating penalizing China over its persecution of Uighur, a predominantly Muslim minority residing mainly in China’s northwestern Xinjiang Province.

Also at the opening meal of the Osaka G-20 meeting in June 2019, as only translators present, Xi stated to Trump why he was essentially building internment camps in Xinjiang. As per our translator, Trump claimed that Xi was planning to establish the settlements, which Trump felt was just the best thing to do. The top Asian member of the National Security Council, Matthew Pottinger, told me that Trump said something really comparable all through his trip to China in November 2017.

Trump became especially peevish about Taiwan, started listening to Wall Street funders who had made wealthy deposits in mainland China. One of Trump’s preferred analogies was to figure to the tip of one of his Sharpies and say, “This is Taiwan,” then point to the historic Oval Office Resolute Desk and say, “This is China.” So much for American obligations and commitments to another democratic alliance.

So much storm came from China in 2020 with the corona virus pandemic. China deferred, concocted and false statements on the illness; repressed dissension from doctors and many others; hampered attempts by the World Health Organization and many others to obtain correct info; and involved in effective propaganda campaigns to assert that perhaps the new corona virus did not occur in China.

There had been a lot to dislike in Trump’s reply, beginning with both the regime’s early, unrelenting statement that perhaps the illness was “stored” but would have little or no financial consequences. Trump’s reflexive effort to charm his way out of something, including the public-health issue, further threatens his and the nation ‘s reputation, with his remarks sounding more like tactical damage management than sound public-health guidance.

However, the other criticisms of the regime were trivial. This one grievance was directed at the part of the general revamping of NSC staff that I carried out in my first months at the White House. In order to reduce duplication and overlap and better understanding and effectiveness, good management made sense in shifting the duties of the NSC bureau on global health and bio defense to the directorate on biological, chemical and nuclear arms. Bio weapon assaults and pandemics could have a lot in common, and the medical and public health experience needed to deal with both risks falls in line.

Almost all of the employees working in the previous Global Health Directorate obviously shifted to the cumulative directorate and proceeded to do precisely what they had done previously.

At best, the inner configuration of the NSC became the wings of a butterfly in the storm of Trump’s turmoil. Given the disdain at the top of the White House, well-known NSC workers did their research during the disease outbreak, proposing choices like shutdowns and social distancing well before Trump did so in March. The NSC Biosafety Team was working exactly as it was supposed to. It was the seat that was vacant behind the Resolute desk.

Trump has taken a sudden turn to anti-China populism in today’s pre-2020 election environment. Irritated in his quest for a new trade agreement with China, and fatally scared of the adverse political impact of the coronavirus pandemic on his re-election chances, Trump has now chosen to blame China with sufficient excuse. It is unchanged to be seen whether his actions match his words. His government has suggested that Beijing’s repression of dissension in Hong Kong would have repercussions, but no concrete penalties have yet been enforced.

Perhaps notably, can Trump’s new China stay question after election day? Trump’s administration is not focused on ideology, the grand scheme of legislation. It’s based on Trump. It’s something to think about for some, particularly the Chinese pragmatists, who feel they know what they’re going to be doing in the second term.

— Oh, Mr Bolton, former U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations, represented as National Security Advisor from April 2018 to September 2019. This article is adjusted from his upcoming book, “The hallway in which it Happened: A White House Memoir,” which Simon & Schuster will submit on June 23.